Reported cargo thefts rise sharply, and that’s just part of the story

The trucking industry is facing a sharp increase in cargo theft, even as insurance providers and police forces say the crime is underreported by those who suffer the losses.

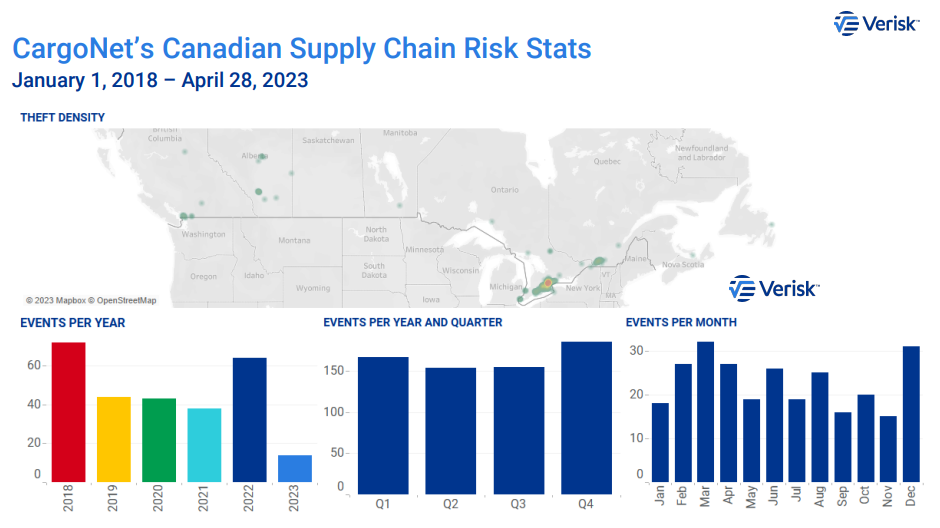

Since last year, cases of cargo theft increased nearly 80% in Canada and the U.S., says Keith Lewis, vice-president of operations at Verisk’s CargoNet, which reports thieves stole $223 million worth of freight in 2022. Trucking-related fraud cases are up 700%.

In Canada alone, reported cargo losses increased 29.8% last year, compared to 2021, says Bryan Gast, vice-president — investigative services at Équité Association. Ontario continues to see the highest activity, accounting for 62% of total recorded cargo thefts in the country.

Even four months into 2023, Gast says, “It’s been a busy year so far.”

He adds that Ontario’s Peel Region remains a hot spot, with Brampton and Mississauga as one of the top areas for cargo thefts in North America.

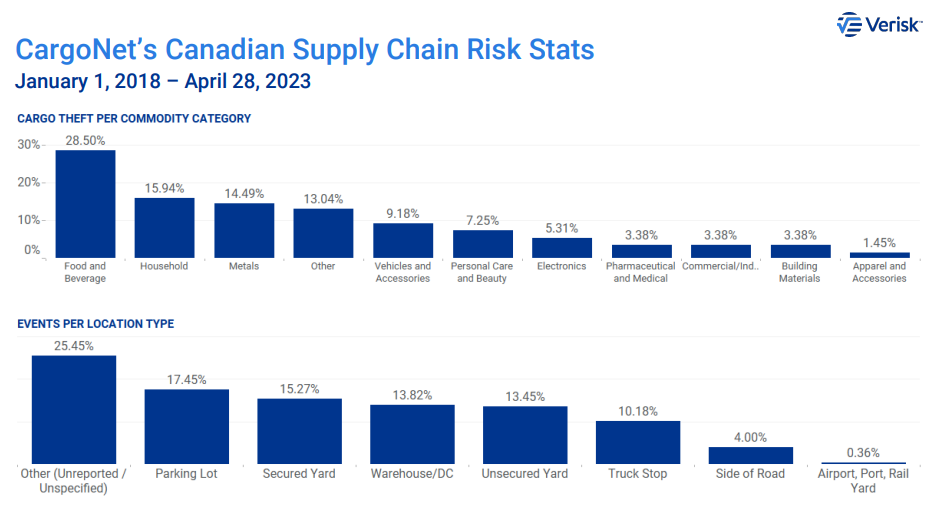

However, Équité has seen that crime cascading beyond the GTA and into Quebec, Montreal, Calgary, Edmonton, Surrey and Winnipeg. Most of today’s targeted cargo includes mixed loads, groceries, and automotive loads.

And while thieves tend to operate in major industrial hubs with dense populations and lots of commerce, a lot of crimes were provoked by parked loads. Especially during Covid-19.

“A load at rest is a load at risk,” says Gast.

“We are playing checkers and the bad guys are playing chess.”

– Keith Lewis, CargoNet

One of the other patterns, seen in both Canada and the U.S., explains the 700% increase in fraudulent activity. Thieves are now expanding their networks by setting up dispatch centers in different countries, making it hard for law enforcement and prosecutors to serve subpoenas, search or arrest warrants, or simply conduct an interview.

And such thieves and fraudsters are getting smarter.

“We are playing checkers and the bad guys are playing chess,” says Lewis.

How stolen loads are unloaded

While thieves and fraudsters may operate from abroad, the actual stolen loads rarely cross the border. Lewis says most stolen goods are unloaded closer to home: “There’re so many places to sell the commodities here [in the U.S.]. As there are in Canada, there are so many avenues to move stolen products [within] either country.”

Criminal groups are particularly effective at the task, Gast says.

“They’re very efficient at their ability to disseminate or distribute their loads. As I said, they’re very quick, they’re a very good network.”

Fresh produce like groceries is usually gone within two days, sometimes even two to 10 hours after a load is stolen, says Detective Sukhdeep Brar of the York Regional Police Auto Cargo Theft Unit.

The biggest challenge within an investigation is trying to recover everything in five to six days. After that, the probability of recovery is very low.

Gast agrees, saying it is easier to recover stolen tractor-trailers than the loads themselves.

Random and targeted thefts

While the criminals may operate in an organized way, between 50% and 60% of Ontario’s cargo theft is random, says Brar.

“You will see a lot of drug users, they steal a load because they need quick money. They steal a load [worth] $100,000 and they will sell it for $5,000. So, these are the people who won’t target [a specific load]. They will do a random steal. They drive around in a stolen car, they go from one yard to another yard…These are random loads. And it could be anything,” he explains.

The remaining thefts, though, are decidedly more organized.

Brar refers to the recent Project Copperhead that York Regional Police launched last December. Earlier this month, its Auto Cargo Theft unit successfully recovered $1.65 million in cargo, leading to 18 criminal charges for four men. In this case, the criminal group based out of Brampton was targeting companies that haul metal.

“They will drive all the way west to Windsor, they will go to Waterloo, and then they will see what kind of loads are parked. And once they have that intel, they go at nighttime and they steal it,” Brar explains. “Most copper loads are over $200,000 and they get 35% or 40% of it…So, if they steal just one load of copper, they can get $70,000-$80,000 in one night.”

‘Cross dock’ operations

It can be easier to investigate larger crime rings than tackling individual losses, too. Goods lost through one-off thefts are often sold before police learn about them. At the very least, the cargo is moved into hiding.

Brar explains thieves often establish a cross-dock, moving cargo from a stolen trailer into a “clean” trailer that is parked somewhere else in a yard, where it is harder to find. Another common practice involves taking a stolen load to a different jurisdiction, where it “cools off” before being sold to a buyer in yet another jurisdiction.

The multiple jurisdictions can make it difficult to report the theft, Lewis says.

“A lot of times we don’t know exactly where the cargo was stolen. And law enforcement agencies are not going to be willing to take a report unless you 100% know that freight was stolen from there. Because they don’t want to put that theft in their jurisdiction if it really wasn’t stolen there.”

And under-reported crime

This might be one of the factors that lead to underreporting, which — according to Brar, Lewis and Gast — is a major issue across the industry.

While Lewis believes both Canada and the U.S. suffer from a lack of enforcement and mandatory reporting, Gast says many carriers abstain from reporting thefts because they don’t want competitors to know the information or worry about losing insurance coverage.

Brar says the latter situation is particularly troubling. He recalls one case where a company went bankrupt after losing four full loads of meat. The loss of one full load usually costs between $200,000 and $300,000, and insurers might end coverage if losses climb too high.

Carriers might choose to absorb a loss worth less than $50,000 – the value of a typical load, Brar says. And when they do, the true extent of thefts remains unknown.

“I’m going to caution you on relying heavily on statistics when there’s no mandatory reporting,” Lewis warns.