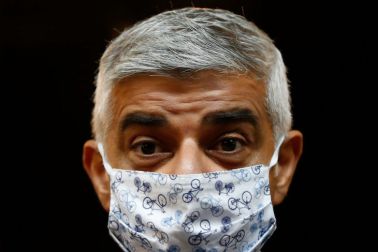

Could Ulez lead to Sadiq Khan’s downfall?

Emmanuel Macron has spoken of his fear of France’s ‘fragmentation’ and of the nation’s ‘division’ following the riots that reduced parts of the Republic to rubble earlier this month. The truth, as the president well knows, is that France is already deeply divided, and the fractures are numerous. As well as the topical one, that of the chasm separating many of the Banlieues from the rest of the Republic, there is also the growing gulf between those who prostrate themselves at the altar of Net Zero and those who are sceptical or downright resistant. And the French, being French, have never been shy in demonstrating forcefully their opposition to the Green zealots.

Ross Clark declares in The Spectator[1] this week that England’s ‘great motorist rebellion’ has begun, a backlash against Sadiq Khan’s expansion in London of Ulez (Ultra Low Emission Zone). The English, being English, have so far demonstrated their opposition peacefully at the ballot box; according to Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer, his party would have won Thursday’s Uxbridge by-election had it not been for Ulez.

Sadiq Khan should ponder Griveaux’s fate

For the moment Khan is defiant, claiming that his decision to expand Ulez ‘was a tough one, but it’s the right one’. The London mayor is saying he is in ‘constructive listening mode’, but he’d better start listening soon. One wonders if the mayor of London is familiar with the name Benjamin Griveaux; he may not be because the Frenchman’s political career never recovered from an infamous remark he made in October 2018. Macron, elected eighteen months earlier, had announced an eco-tax that would increase the price of diesel fuel, bad news for those French who lived in the sticks and relied on their vehicle for work.

These men and women voiced their opposition on social media and on the airwaves, but their concerns were contemptuously brushed aside. ‘People who smoke cigarettes and drive diesel cars,’ sniffed Griveaux, the government spokesman, ‘…are not the 21st-century France we want’.

As I wrote at the time in Coffee House[2], ‘Macron may come to regret this insouciant rhetoric’. Sacre Bleu, was that an understatement. Within a couple of weeks men and women wearing high-visibility yellow vests were descending on Paris; a few thousand at first, but by Christmas 2018 there were hundreds of thousands, not just in Paris but in many towns and cities across the Republic. What was most impressive, however, the true sign of the demonstrators’ anger and the determination was the men and women who camped out throughout the winter at roundabouts and other locations. I recall seeing one such group at a roundabout in Aveyron – real France Profonde – on Christmas Day. Had I been Macron or one of his ministers I would have been unsettled by such ferocious commitment.

Most popular

Julie Burchill[3]

Sadiq Khan needs to #HaveAWord with himself

The eco-tax wasn’t the only reason the provinces were up in arms; in July 2018, the government had reduced the maximum speed limit on French highways from 90km/h to 80. They claimed it was to improve road safety, even though ministers knew from the outset that the measure was unpopular.

One poll in 2015 asked the question if the limit should be lowered to 80km/h and 77 per cent responded in the negative. There were fears that such a reduction would be the first of many, but also a suspicion that it was a cunning ploy to fleece drivers.

‘We can’t let the State implement such a measure,’ said Pierre Chasseray, the head of one automobile organisation. ‘By lowering speed limits on the secondary network and privatising the speed cameras, it would be a jackpot for the State, which would reap the maximum amount of money.’

Furious with the Paris political class, the people went to war against the speed cameras. Between January 2018 and August 2019, nearly 20,000 were put out of action. Some were burned, others spray-painted and numerous cameras were ripped down completely.

‘The outcry is strong because it is such a tangible issue for ordinary people,’ Jérôme Fourquet – one of France’s leaders pollsters – told the BBC. ‘Around 70 per cent of the population is opposed, and there is no sign of that abating.’

The government’s initial response was to remind citizens that the cameras were there for their own good; when the nannying approach didn’t work, threats of heavy fines and prison sentences were made. They also failed to bring about an end to the speed camera cull. Indeed by this time, Paris was awash with yellow vests and a chastened president Macron was telling the nation he understood their anger. To placate protestors the eco-tax was scrapped and France’s 96 départments were authorised to restore the speed limit to 90 km/h should they wish; 46 have, mostly rural départments where the car is king.

Unlock unlimited access, free for a month

then subscribe from as little as £1 a week after that SUBSCRIBE [4]As for Benjamin Griveaux, he left the government in March 2019 and, after a failed attempt to become mayor of Paris, quit politics in 2021.

Sadiq Khan should perhaps ponder Griveaux’s fate because it transpired that his vision of 21st century France wasn’t shared by the majority of the people, and as every politician ultimately discovers the will of the people always win out.

References

- ^ The Spectator (www.spectator.co.uk)

- ^ Coffee House (www.spectator.co.uk)

- ^ Julie Burchill (www.spectator.co.uk)

- ^ SUBSCRIBE (www.spectator.co.uk)