How were the 39 people killed in the Essex lorry case identified?

The 39 people who died in the back of a trailer as it crossed the North Sea between Zeebrugge and the UK Four years ago, the bodies of 39 Vietnamese nationals were found in an airtight container on the back of a lorry[1]. For the first time, those involved in the investigation tell how tattoos, fingerprints and hidden telephone numbers helped them piece together the identities of the victims.

At 06:00 on 23 October, 2019, Deidre Nowell, the casualty bureau manager for Essex Police, was already in her car. While driving she received a call telling her a large number of bodies had been found in the back of a refrigerated trailer in Grays[2], Essex. The trailer arrived in the UK via the Belgian port of Zeebrugge and reports of what officers encountered at Grays were simply "overwhelming", Mrs Nowell said.

Deidre Nowell has worked on a number of major incidents.

Although she had been involved in a number of major incidents during her lengthy career, this was her first mass casualty incident in Essex as bureau manager. While detectives worked to piece together what had happened and who might be responsible, another team worked around the clock trying to identify the victims, none of whom had any identification on them. At first, police thought all 39 people found in the trailer were Chinese.

But then a Vietnamese interpreter revealed they had started to receive messages about Vietnamese people who might be among the victims. In the hours and days that followed, it emerged that all of those who perished in the trailer were not from China at all, but from Vietnam.

The casualty bureau was set up in a hall area known as "The Pit". It is currently used as a training and instruction area by Essex Police

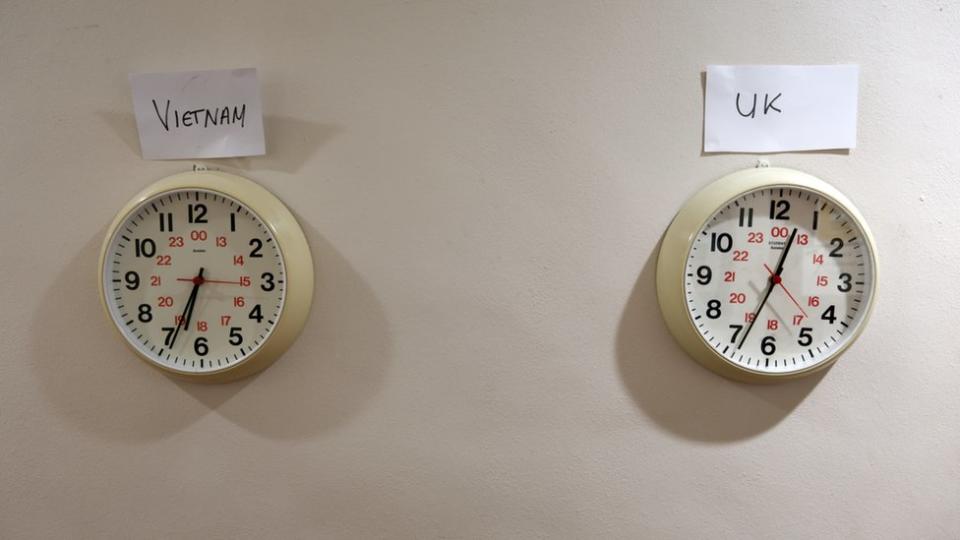

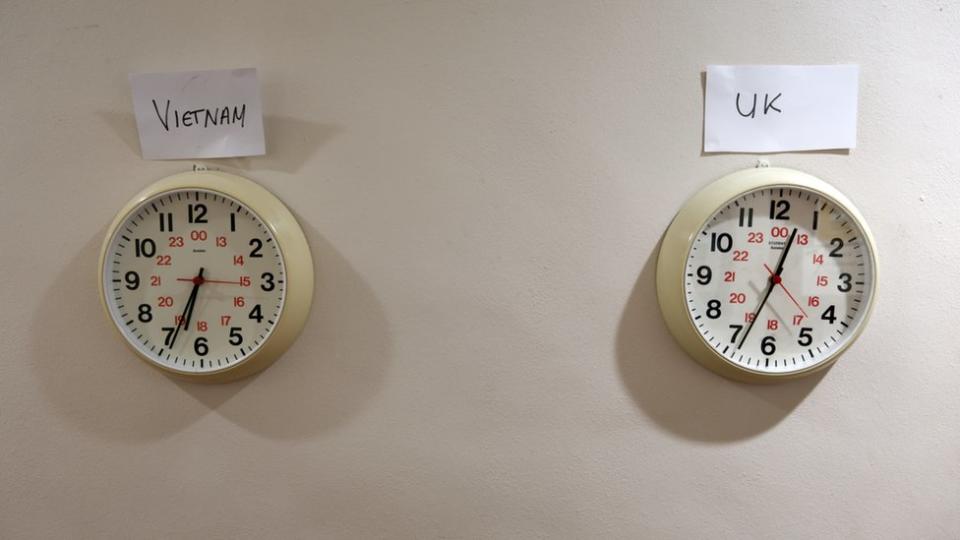

A casualty bureau brings specially-trained staff and police officers under one roof to act as the focal point for information about a mass fatality incident to be received and assessed. The Essex lorry deaths case bureau was set up in a hall previously used as the force control room, known as "The Pit". Once it was discovered that most, if not all, of the victims were Vietnamese, a clock showing the time in Vietnam was put up alongside the UK time clock.

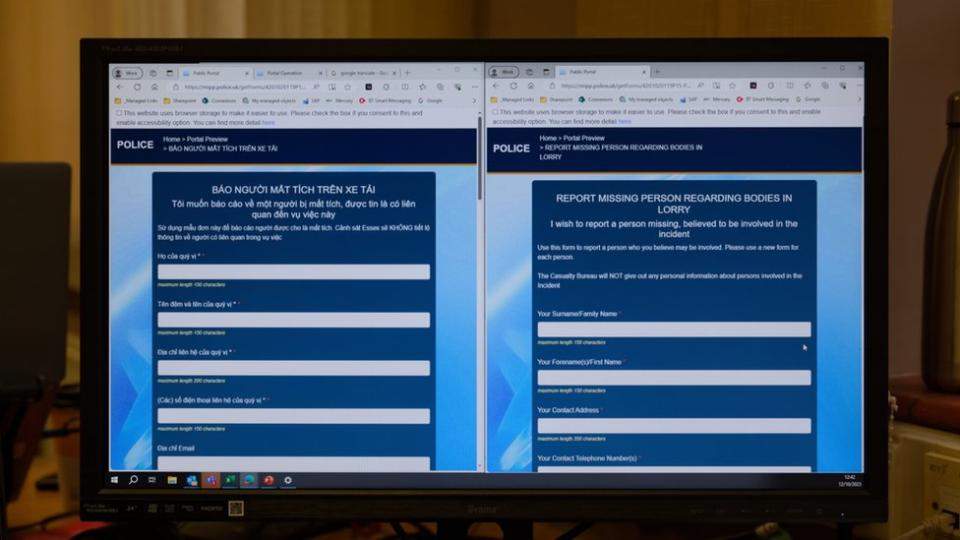

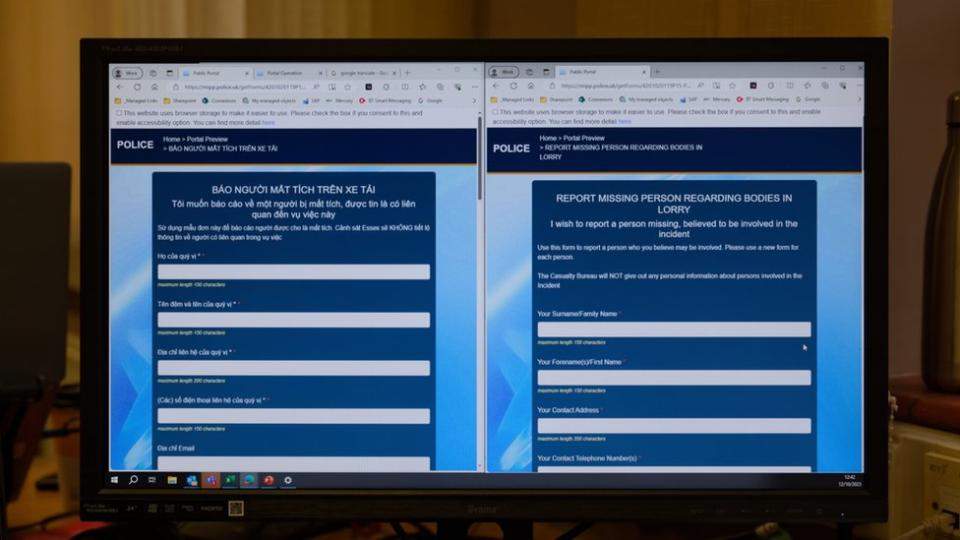

Mrs Nowell said: "We realised, because of the time difference between the UK and Vietnam, that our call centre had to be going a lot longer each day." Story continues The lorry deaths case - called Operation Melrose in police circles - was the first time a police information system called the Major Incident Public Portal[3] (MIPP) was used to gather information from the public for a mass fatality incident or when a casualty bureau had been set set up.

MIPP was developed in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombings, which had shown the importance of gathering public information, video footage and images as quickly as possible. "It became absolutely fundamental," said Mrs Nowell. "We started to get messages through and the families were sending us ID cards which, in Vietnam, have images of fingerprints on the reverse side."

The MIPP was offered in both Vietnamese and English

The casualty bureau's work was not without its issues, however. Staff initially found they could not make international calls and their keyboards could not be used to type in Vietnamese. The team, which grew to include hundreds of trained colleagues from both Essex and other police forces, also realised they had an issue with members of the public phoning in and then hanging up.

These were not prank calls. These were Vietnamese callers ringing in, listening to a welcome in English which meant nothing to them, and then understandably ending the call. The moment the penny dropped, a corresponding welcome message in Vietnamese was recorded while call handlers found themselves paired with Vietnamese translators, said Michelle McHugh, the deputy bureau manager.

"Every time we managed to identify one of the people we would put their photograph up on the wall," said Michelle McHugh, the deputy bureau manager for Essex

"We then took the details of the casualties that we had and matched them up with other details," Mrs Nowell said. Key to identifying the victims was a team called the reconciliation unit, which was housed away from the main bureau base in a previously empty temporary building. Inside there was a whiteboard on which all 39 post-mortem reference numbers were written.

On another whiteboard was the rapidly growing list of the possible names of victims. One of the victims was identified by his teeth after it was matched with a photograph supplied by family of him smiling. Others were identified using distinctive tattoos, telephone numbers written on the inside of belts and hats or their fingerprints.

"Every time we managed to identify one of the people we would put their photograph up on the wall," said Mrs McHugh. "Our job is to give people back their names and identity."

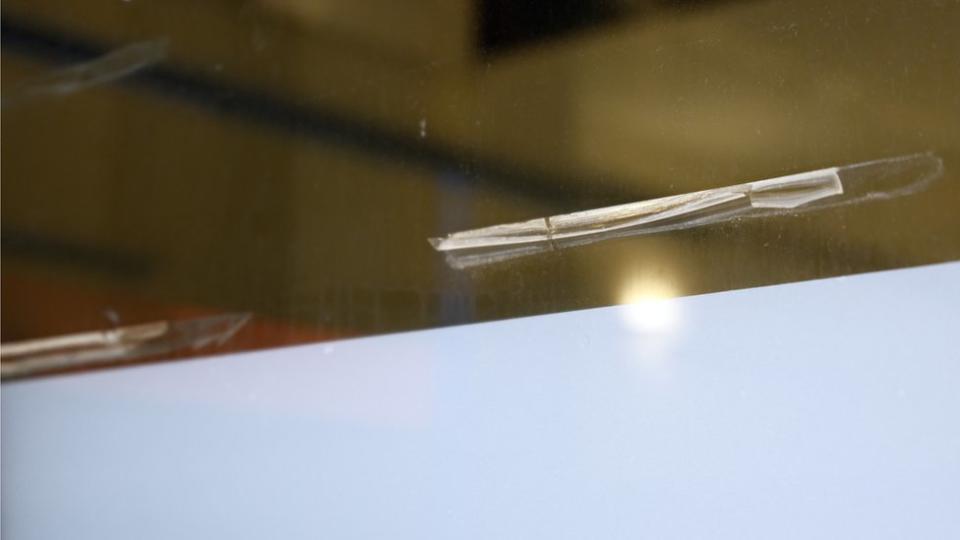

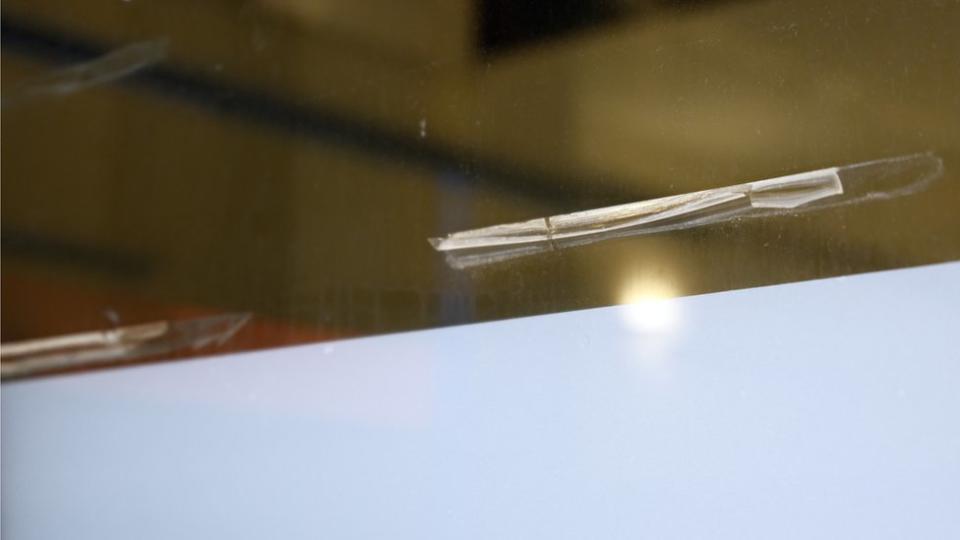

Traces of gum used to put the pictures of the victims up once identified still remain on the glass wall of an area called "The Pit" at Essex Police's Chelmsford HQ Identifying each victim is an intensely detailed process that involves matching up two separate types of evidence. On one side is all the evidence gathered for each of the dead victims, on the other is all of the missing person evidence.

Detectives are then paired up to carry out what the bureau calls "comparative case analysis". The process starts with gender, an approximate age and the clothing a person was found in before moving on to marks, scars, tattoos and jewellery. At this stage detectives are trying to build up a set of possible matches before the scientific evidence - DNA, fingerprints or dental evidence - comes back.

Melissa Dark, who coordinates the UK's National Casualty Bureau, was attached to Essex during Operation Melrose

Melissa Dark, who coordinates the UK's National Casualty Bureau, said: "We never make assumptions in these cases and only build files on the factual evidence. "If we don't have the evidence to build a file - we simply don't build it and wait for the science to tell us who individuals are." Once the scientific evidence puts the victim's identity beyond doubt, it is signed off by a so-called reconciliation manager and sent first to a senior identification manager who presents the evidence to an Identification Commission, which is chaired by a coroner.

'Two weeks and one day'

That wall of photographs gradually filled up until all 39 were there.

The victims were 28 men, eight women and three children. They were aged between 15 and 44 years old. "Eventually there were no names on the missing person white board and each reference had a name and picture next to it," says Ms Dark.

The process of naming all 39 people who had set off from the other side of the world and arrived in Essex with no identification documents was complete. The process of identification had taken two weeks and one day. The reconciliation room was silent, with Ms Dark and two detective sergeants momentarily lost for words.

In the casualty bureau's operations room, a clock showing the time in Vietnam was put up on the wall

"Putting that last name up on that board, and seeing in front of you 39 hard copy bound files with the photos of the missing persons, was breath-taking and incredibly moving. "At the end of that very long shift the deputy senior identification manager came to collect the files to take to the ID Commission the next day. "I know she was up all night reviewing the files so she knew each and every victim and learning how to pronounce every name correctly to give the upmost respect and dignity possible in the ID commission.

"It makes me emotional thinking about that now. "It will be one of the proudest days of my career and I will never forget any of those families and victims - they are forever etched onto my soul." Ms Dark then turned to the rest of the team to share the news that everybody had been successfully identified.

Those involved were debriefed, released from the reconciliation unit and returned to their normal policing roles.

Ms Nowell tells of the "immense relief" she felt after all 39 victims were identified As for Mrs Nowell, she describes a sense of immense relief. "In my world, it meant the job was done and we had achieved everything we had set out to," she said.

"And, yes, I cried - but only after our job was done." Four men - Ronan Hughes, Gheorghe Nica, Eamonn Harrison and Maurice Robinson[4] - were jailed for manslaughter in 2021. A further seven have been imprisoned in connection with the deaths.

One further defendant is expected to go on trial later this year accused of conspiracy to assist illegal immigration. Follow East of England news on Facebook, Instagram and X. Got a story?

Email [email protected] or WhatsApp 0800 169 1830[5][6][7]

References

- ^ back of a lorry (www.bbc.co.uk)

- ^ Grays (www.bbc.co.uk)

- ^ Major Incident Public Portal (mipp.police.uk)

- ^ Ronan Hughes, Gheorghe Nica, Eamonn Harrison and Maurice Robinson (www.bbc.co.uk)

- ^ Facebook (www.facebook.com)

- ^ Instagram (www.instagram.com)

- ^ [email protected] (ca.news.yahoo.com)