Letter carriers face bullets and beatings while postal service sidelines police

CHICAGO — As a little girl in the 1980s, Khalalisa Norris aspired to become a letter carrier. She’d sit on her front porch in Chicago’s Austin neighborhood and wait for her local mailman, and eventual mail lady, each day.

In her 20s, Norris realized her dream, and ever since, she’s delivered mail on Chicago’s West Side.

But that dream became a nightmare.

Norris was working an overtime shift in the Austin neighborhood when she saw two men run past her toward a corner liquor store. As Norris exited an apartment building and returned to her mail cart, one man jumped in front of her, stopping the cart and pointing a gun in her face. The other walked alongside her and stuck a gun to her temple.

Both had their fingers on the trigger and said “we just want the keys,” Norris, now 46, told Raw Story[1] in an exclusive interview. Norris took her set of arrow keys — the universal keys letter carriers use to open blue letter boxes that dot America’s street corners — and threw them at the robbers.

Norris froze in place until the criminals fled, fearing that if she attempted to run, they would “shoot me in my back.”

The violent day in January 2023 left Norris traumatized and changed.

“They took more from me than just those keys,” she said.

Norris’ ordeal is becoming too common: Letter carrier robberies skyrocketed by 543 percent between 2019 and 2022, according to a February 2024 United States Postal Service publication[2].

Such lawlessness and violence has made the job of letter carriers — once coveted for its government benefits and respected for its service to America since the country’s founding — an increasingly hazardous job.

Mail carriers, especially those such as Norris who’ve been assaulted[3], want their federal government employer, the United States Postal Service, to do more — much more — to protect them.

That, however, may not be possible because of restrictions on who can actually patrol the streets where letter carriers work.

Because of a 2020 statute reinterpretation[4] from the Postal Service, its own dwindling uniformed police force of 450 officers no longer patrols streets where letter carriers like Norris deliver the mail.

Instead, postal police officers, whose numbers exceeded 2,600 in the 1970s, are relegated to only working on postal properties, such as neighborhood post offices and regional distribution centers. This shift in policing responsibilities, largely unknown to the general public, has embroiled the Postal Service and the Postal Police Officers Association union in a four-year-long dispute that remains unresolved.

Mail robberies, meanwhile, take a hefty financial toll on citizens and financial institutions alike, contributing to nearly $100 million in stolen checks per month, according to research from David Maimon, a professor who runs the Evidence-based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University.

“We have nobody. We’re out there by ourselves. We can get accosted and jumped,” said Elise Foster, a letter carrier and president for the Chicago branch of the National Association of Letter Carriers. “They can, with a gun, do whatever they want.”

Norris, union leaders and criminologists tell Raw Story[5] the solution is simple: The United States Postal Inspection Service — the law enforcement arm of the Postal Service — should use its uniformed postal police officers on mail routes to deter criminals.

Yet, the agency currently refuses to put its postal police officers back in the streets, arguing that doing so increases liability. Its separate postal inspector force, as opposed to rank-and-file officers, can protect carriers, the agency contends.

So far, that hasn’t been the case, postal employees tell Raw Story.

Rising crime against letter carriers

Mailbox arrow keys are a prized commodity among criminals. Thieves are brazen in their pursuit of them. Steal one, and you can access street-side mailboxes and mailboxes in communal buildings that are filled with packages, credit cards, checks, cash and personal information to create fraudulent accounts.

Yes, a single arrow key can indeed open multiple blue boxes and communal mailboxes in a given area, half a dozen postal employees confirmed to Raw Story.

Criminals sell arrow keys, as pictured, for thousands of dollars on black market websites. This screen grab from the dark web, obtained by the Evidence-based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University, shows arrow keys in California being sold for $1,500 last year. (Photo courtesy of David Maimon)

Criminals sell arrow keys, as pictured, for thousands of dollars on black market websites. This screen grab from the dark web, obtained by the Evidence-based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University, shows arrow keys in California being sold for $1,500 last year. (Photo courtesy of David Maimon)

The mail has become “another avenue for bad actors to try and enrich themselves,” said Spencer Block, a postal inspector and public information officer at the Chicago division headquarters of the United States Postal Inspection Service.

Between the 2019[6] and 2022[7] fiscal years, robbery investigations jumped from 94 to 423 nationwide, according to the U.S. Postal Inspection Service’s annual reports.

During fiscal year 2022, fewer than one in four robbery cases resulted in arrests, and fewer than one in six ended in a conviction, according to the U.S. Postal Inspection Service’s annual reports[8].

Letter carrier robberies, specifically, grew more than sixfold, increasing from 64 cases in fiscal year 2019 to 412 in fiscal year 2022, according to the February 2024 edition of The Eagle[9], the quarterly magazine for Postal Service employees. There were 326,760 letter carriers employed by the Postal Service as of mid-2022, according to. the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics[10].

“Our presence wasn't carrying the weight that it once had in terms of … we're federal employees and nothing’s going to happen to us,’” said Mack Julion, a letter carrier and assistant secretary-treasurer for the National Association of Letter Carrier. “They're not afraid to rob, to assault, to do whatever. If they're involved in criminal activity, we're not hands off.”

Postal police officer patrols used to deter criminals while letter carriers delivered their routes, five postal service employees told Raw Story.

Norris remembers six or seven years ago when postal police officers would still sit in patrol cars marked with the U.S. Postal Service logo in high-crime areas. Sometimes, they got out of their vehicles and walked around in uniform. They carried guns and could make arrests. They could escort a letter carrier if the letter carrier feft unsafe.

A postal police officer in Detroit greets a letter carrier. (Photo courtesy of the Postal Police Officers Association)

A postal police officer in Detroit greets a letter carrier. (Photo courtesy of the Postal Police Officers Association)

Now, Norris said criminals “don't feel or see their presence.” She and her fellow letter carriers are in “survival mode” when they do their jobs. She estimated she hasn’t seen a postal police officer on the streets since 2017 or 2018 — at the very least since the COVID-19 pandemic started four years ago.

“Once they stopped seeing them, that's when the crime went up, especially with the taking of the arrow keys, robbing us at gunpoint,” Norris said. “They made it very easy and convenient for them because they would rob one area, go to the next. By the time they figure out from the carrier that got robbed at gunpoint, they will be in another ZIP code doing it again.”

The limitations on postal police officers go as far as prohibiting them from intervening if they witness an assault or crime off postal property, postal employees told Raw Story.

“They tell us to keep going and call Chicago police. Just call 911,” said Marlon Barber, a postal police officer since 2019, who works downtown.

It’s not just Chicago where letter carriers are under attack. It’s a problem from Salt Lake City to Miami, where mail carriers are also being robbed, Julion said.

In 2022, two men allegedly shot and killed[11] letter carrier Aundre Cross as he delivered mail in Milwaukee[12]. Four individuals have been charged in relation to the alleged “targeted attack,” according to Milwaukee TV station WTMJ 4[13].

Crimes against letter carriers are less likely to be seen outside of cities, with the vast majority occurring in major metro areas, but suburbs and rural areas have experienced crime too, according to news reports compiled by the Postal Police Officers Association union.

ALSO READ: Inside the neo-Nazi hate network grooming children for a race war[14]

John Cruz, a letter carrier and president of the National Association of Letter Carriers’ Brooklyn and Staten Island branch in New York, said it’s “tough time right now” for letter carriers who are often “scared” and “frustrated” with their jobs. It also comes during a period of significant turbulence for the Postal Service, which is in the midst[15] of a[16] massive, and controversial reorganization[17] amid ongoing financial difficulties[18].

Cruz said a letter carrier in Brooklyn, N.Y.’s Brownsville neighborhood was assaulted on the job during a robbery — she was hit on the head where she had a previous surgery wound.

Now, she doesn’t want to return to work, especially since the alleged assailant has been released from jail.

“They want to go home to their family the same way they walked in. Safe,” Cruz said. “Unfortunately, we don't even know what's going to happen today or tomorrow.”

Members of the Postal Service Board of Governors, an 11-member governing body whose members are nominated by the president[19] and confirmed by the U.S. Senate, were not made available for interview, including Postmaster General Louis DeJoy.

Surging check fraud

The Postal Service itself acknowledged that it finds itself in the midst of a “crime wave.”

This entails a ”significant rise in mail theft and crimes against postal employees,” according to the February 2024 edition of Postal Service's magazine, The Eagle[20].

“High-volume theft from mail receptacles” increased by 87 percent between 2019 and 2022, rising from 20,574 reports to 38,535 reports, the magazine said.

Yet, as mail thefts skyrocketed, related arrests declined nearly 40 percent between 2019 and 2022, according to Postal Inspection Service annual reports.

In fiscal year 2022[21], there were 1,124 cases of mail theft with 1,258 arrests — some cases involved multiple suspects — and 1,188 convictions.

By comparison, in fiscal year 2019[22], there were 1,278 mail theft cases, 2,078 arrests and 2,067 convictions.

The U.S. Postal Service Office of Inspector General — an independent entity that investigates fraud, waste and abuse in the postal agency — published a critical report[23] in September about the Postal Service’s response to mail theft.

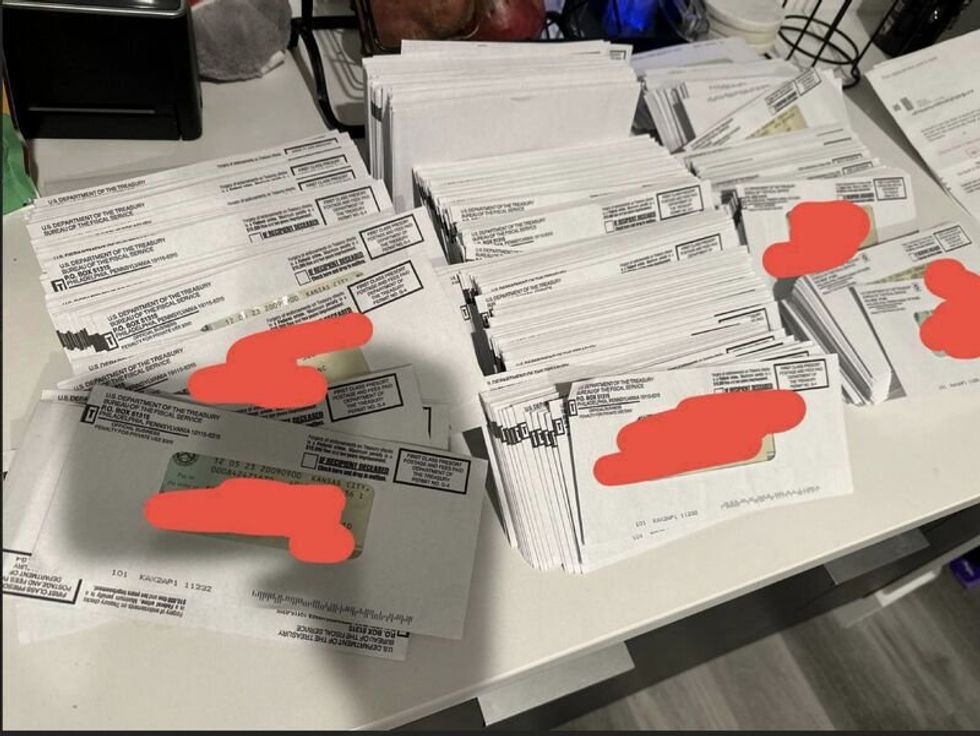

A photo of piles of U.S. Treasury checks in Philadelphia appears on the dark web, obtained by the Evidence-based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University, which crossed out personal information. (Photo courtesy of David Maimon)

A photo of piles of U.S. Treasury checks in Philadelphia appears on the dark web, obtained by the Evidence-based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University, which crossed out personal information. (Photo courtesy of David Maimon)

The Inspector General report found that while the Postal Service is attempting to improve security measures around collection boxes and arrow keys, the efforts aren’t enough to effectively thwart mail theft. The Postal Service, investigators wrote, lacked “actionable milestones” for its mail theft initiatives, faced challenges with staffing to address the issue and hadn’t defined a purpose for its Mail Theft Analytics Program.

Perhaps most notably, the report said the Postal Service “lacks accountability for their arrow keys, which are often a target in carrier robberies and are used to commit mail theft.”

Postal Service leaders submitted a written response to the Inspector General’s report, in which they disagreed with four of seven recommendations, including having the chief postal inspector assess staffing resources for the mail theft program and making a plan to “fully deploy eArrow locks” — electronic versions — and “high security mailbox initiatives.”

Tara Linne, a spokesperson for the U.S. Postal Service Office of Inspector General, said its recommendation to evaluate “proposed quantities, projected cost and actionable milestones to fully deploy mail theft measures, including high security collection boxes and eArrow locks,” remained open as of March 14.

“Our office is seeking additional information from the Postal Service regarding their proposed actions through our audit resolution process,” Linne said.

Block, of the United States Postal Inspection Service, told Raw Story in a phone interview that mail theft is the “bread and butter” of the U.S. Postal Service’s investigations.

“Our overall mission is to ensure the sanctity and integrity of the mail and of the Postal Service to make sure that the public has confidence that when they put something in their mailbox that it's going to end up at its final destination, and by a significant margin, it does,” Block said.

ALSO READ: Racism, arrests, extreme MAGA love: Meet Lauren Boebert’s primary opponents[24]

In February 2023, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, a bureau within the U.S. Treasury Department, issued an alert[25] about “mail theft-related check fraud schemes targeting the U.S. mail.” It noted that the Postal Inspection Service received 299,020 mail theft complaints between March 2020 and February 2021, representing a 161 percent increase from the year prior.

Meanwhile, suspicious activity reports related to check fraud grew by nearly 140 percent between 2019 and 2022, according to a 2023 report[26] from the Thomson Reuters Institute. There were 285,716 such reports in 2019. By 2022, the figure had ballooned to 683,541.

“Criminals increasingly targeted U.S. mail carriers during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the report said, noting that robbers often stole personal checks, business checks, tax refund checks and government checks such as Social Security and unemployment benefits.

“The act of stealing the check and cashing it is just the first criminal thing in a really long, long, long chain of events that victims will be taken for,” Maimon, of Georgia State University, explained.

Maimon, who is also head of fraud insights at SentiLink, a fraud software company for financial institutions, said he saw the problem of mail theft first spike in late 2021 and early 2022, when he conservatively estimated stolen checks totaled in the low eight figures per month. Now it’s close to $100 million per month.

“All the banks are bleeding at this point,” Maimon said. “The criminals are using identities in order to apply for benefits they do not deserve, so the government will start losing money, and they are losing money because we're seeing the criminals taking the identities and applying for tax benefits, tax refunds on behalf of the victims. Everybody's losing.”

Block argued that the theft of personally identifiable information from the mail is “infinitesimal,” and postal customers generally shouldn’t be worried about having their personal information stolen from the mail.

But the Postal Inspection Service does consider check washing[27] — the act of altering information on a stolen check in order to commit fraud — “a big deal,” Block said. The Postal Inspection Service recovers $1 billion in counterfeit checks and money orders each year, according to its website[28]. Postal Inspectors work with bank investigators and use tools to hunt these criminals.

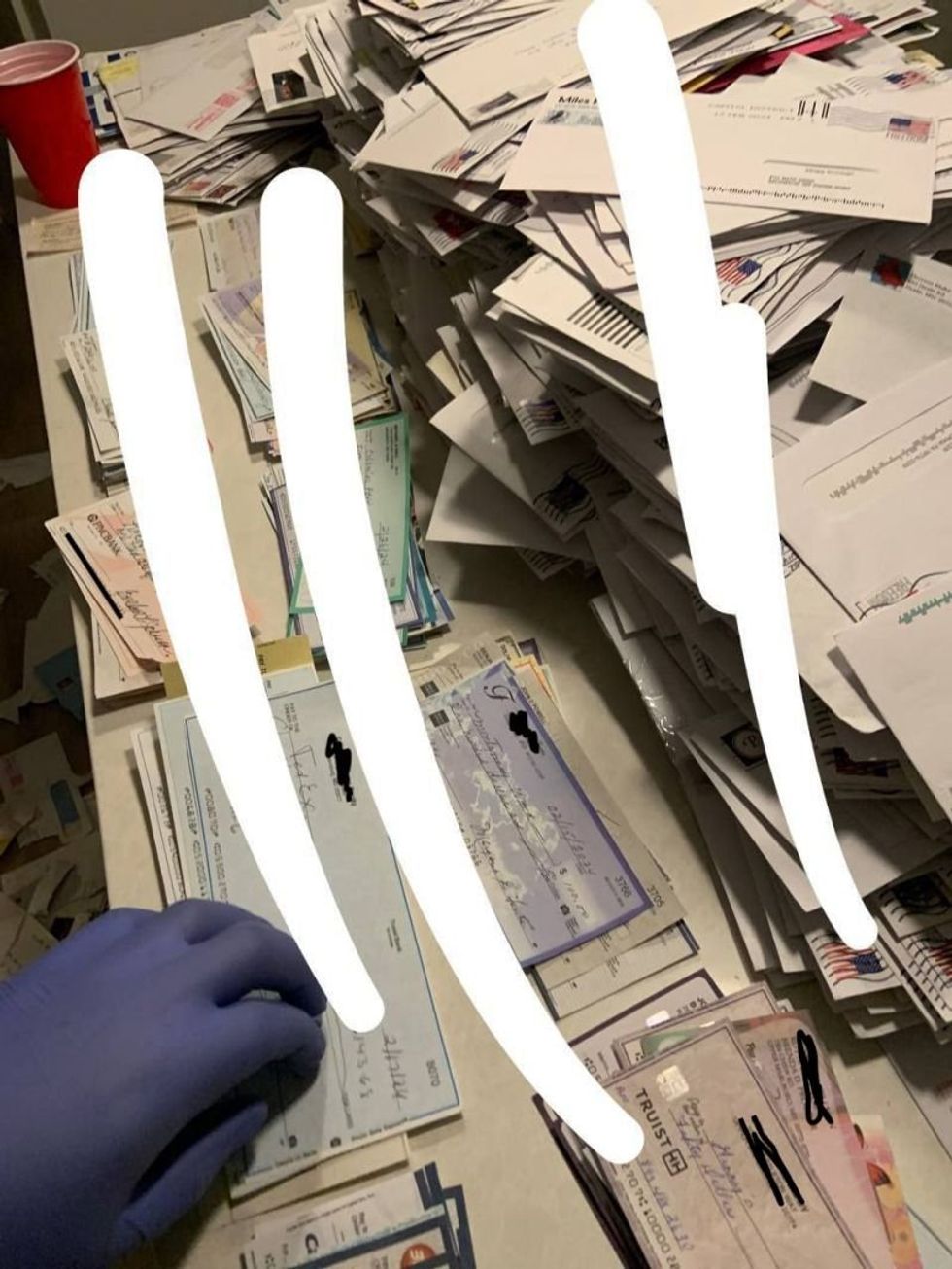

Thieves posted a photo in February from a mail heist in Upper Marlboro, Md., on the dark web, which was obtained by the Evidence-based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University.The researchers crossed out personal information. (Photo courtesy of David Maimon)

Thieves posted a photo in February from a mail heist in Upper Marlboro, Md., on the dark web, which was obtained by the Evidence-based Cybersecurity Research Group at Georgia State University.The researchers crossed out personal information. (Photo courtesy of David Maimon)

How bad have financial crimes via mail theft become?

Rep. Ken Calvert (R-CA) — who is co-sponsoring legislation to increase penalties for mail crimes — lost nearly $10,000 due to mail theft in October[29], Raw Story first reported.

A thief stole from the mail a $3,000 check[30] from the campaign of then-House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) in July 2023.

“We definitely need better protection of our mail in order to make sure that this does not continue, but in addition to that, we need to find a way to prevent USPS customers’ identities from being stolen, being used for other nefarious reasons,” Maimon said.

Where are the postal police?

In August 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic raged and the Postal Service’s finances deteriorated[31], postal leaders made a fateful decision.

David Bowers, deputy chief inspector for the Postal Inspection Service, decreed[32] that postal police officers would no longer be assigned to street patrol. Instead, officers would be stationed only on “real property” — “land and buildings owned, occupied or otherwise controlled by the United States Postal service,” according to a 2020 internal document[33] from a talk given to postal police officers and shared with Raw Story.

Postal police officers previously could patrol high crime areas in neighborhoods and make arrests if they witnessed a crime on the streets.

That’s no longer the case. Today, postal police officers are effectively banned from policing the streets where mail carriers make their rounds and most mail theft occurs.

“Effective immediately, any off property responses to robberies, physical assaults, mail theft or other postal related crimes are prohibited,” the 2020 internal document[34] said.

“They reinterpreted the statute … and basically benched us, which was crazy because that's exactly when postal-related crimes started to rise, and now it's spreading like wildfire across America,” said Frank Albergo, president of the Postal Police Officers Association.

Already, the number of postal police officers had been steadily declining.

In 1974, the federal government employed 2,648 postal police officers. As of 2023, there were 450, according to Albergo, which includes lieutenants and sergeants. The U.S. Postal Service’s Office of the Inspector General said there were 348 active postal police officers with the bargaining unit, as of April 2023.

Postal police officers are located in 20 cities but used to be in as many as 66 in the 1970s and 1980s, Albergo said.

A postal police officer stands on a corner in Detroit. (Photo courtesy of the Postal Police Officers Association)

A postal police officer stands on a corner in Detroit. (Photo courtesy of the Postal Police Officers Association)

The number of postal inspectors has been shrinking, too, but not nearly as much. Postal inspectors decreased from 1,755 in 1974 to 1,259 in 2023, Albergo said.

The main difference between postal inspectors and postal police officers is that inspectors “develop cases and prevent crime while protecting the American public,” where the officers “ensure the security of high-value deliveries, property and postal buildings,” the Postal Inspection Service’s website said.

An appropriate analogy is that postal police officers are like patrol officers and inspectors are like detectives, two postal employees told Raw Story. Postal police officers wear uniforms and drive in marked vehicles, where inspectors are often in plain clothes and unmarked cars.

The Postal Service isn’t the only federal agency to have its only police force — dozens of agencies such as the U.S. National Park Service and Amtrak have their own police.

Until the last decade, most criminals would never dare touch a letter carrier and showed more respect toward postal employees, Norris and Julion concurred.

After all, letter carriers are employees of the U.S. government, and committing a crime involving the mail is a federal felony offense.

“They wouldn't assault us. That was like a big no-no for them,” Norris said. “The community knew you just don't mess with the mailman or mail lady.”

Legal tug-of-war between the postal service and union

The Postal Service said the “legal jurisdiction” for postal police officers did not change in 2020 as a part of the statute reinterpretation, acknowledging that some divisions used to use the police officers off-property, according to Michael Martel, a postal inspector and national public information officer for the United States Postal Inspection Service.

Questions were raised about “whether these patrols conformed to the law and whether they were effective,” Martel told Raw Story via email.

This led to the Postal Inspection Service deciding to “comprehensively curtail” the use of postal police officers “outside the immediate environs of Postal Service real property,” which it says was necessary to protect the officers and Postal Service “more broadly from legal liability,“ Martel said.

In 2020 a federal court dismissed a lawsuit[35] from the Postal Police Officers Association against the Postal Service calling the statute in question “ambiguous” and saying the Postal Service “did not act unreasonably” in its reinterpretation of the statute.

Postal inspectors, not postal police, are responsible for “off-site protection of the mail and our letter carriers” and “regularly conduct surveillance and appropriate enforcement actions in areas where high numbers of letter carrier robberies and mail thefts have been reported,” Martel said.

Postal police officer Jose Fernandez stands outside the James A. Farley Post Office building in New York City on April 15, 2004. (Photo by Monika Graff/Getty Images)

Postal police officer Jose Fernandez stands outside the James A. Farley Post Office building in New York City on April 15, 2004. (Photo by Monika Graff/Getty Images)

But in January 2021, an arbitrator determined that postal police officers’ duties are “very similar to the vast majority of patrol police officers’ duties" and awarded the officers a two-grade salary increase, with raises totaling about $1,700.

“The Postal Service retaliated by eliminating our authority to perform those duties, but obviously, this doesn't make sense because they had already paid for those duties,” Albergo said.

The Postal Service "remains confident in its position" that the law enforcement authority for postal police officers is "limited to postal premises under the law, and no court or arbitrator has disagreed with that conclusion," said David Walton, a spokesperson for the Postal Service, in a statement to Raw Story.

A second arbitration came in 2023, determining[36] that postal police officers have some jurisdiction outside of postal properties and that postal police officers are to be governed by the handbook, not the 2020 memo. However, the arbitrator made clear that "nothing in this award should be construed" as requiring the Postal Service to deploy postal police officers away from postal "real property."

Of postal police officers’ current responsibilities, Block said, they “include physical security at our larger postal plants,” providing a “visible presence in marked cars” and doing station visits at local post offices.

The Postal Inspection Service’s website emphasizes that postal police officers are “a crucial part of the Inspection Service team.”

“Stationed in postal facilities across the nation, they stand on the frontlines in the fight to protect postal employees, customers, and property,” the website[37] said.

“What good are they just guarding facilities? I mean, really, playing like flashlight cops to facilities and literally after-hours checking to make sure the gate is locked and stuff like that?” Julion said.

A 2017 postal police officer job description[38] shared with Raw Story includes responsibilities such as responding to “emergency situations (e.g., burglaries, robberies, natural disasters, medical emergencies, Postal Service vehicle accidents)” and enhancing the Postal Inspection Service’s “community policing, crime prevention and security efforts,” which includes acting as a “visible deterrent to criminal attack.”

In February 2024, a federal court upheld the 2023 arbitration, denying the Postal Service’s motion to dismiss. Albergo called the ruling a “win,” but there’s still been no change in postal police officers’ ability to work off-property, and Albergo said he expects continued resistance.

“This is not about our law enforcement authority. This is not about protecting letter carriers or protecting the mail,” Albergo said. “This is about the Postal Service beating the smallest postal union in a labor dispute. That apparently is more important to them than protecting the sanctity of the mail and the safety of letter carriers.”

The Postal Service disagreed, saying the recent district court decision "did not express a contrary view, but instead merely returned a matter to an arbitrator to obtain clarification of his award, which we believe will be construed favorably to the Postal Service," Walton said.

A separate class action suit[39] was filed against Postmaster General Louis DeJoy in January 2024, alleging that DeJoy “discriminated against Black and Hispanic postal police officers by failing to provide them with the same access to the Postal Service’s Self-Referral Counseling Program as postal inspectors.” Albergo said at least 80 percent of postal police officers are “black and brown.”

What is the Postal Service doing to curb crime against letter carriers?

DeJoy, the postmaster general, insists that the Postal Service is protecting its letter carriers, particularly with its new “Project Safe Delivery” program aimed at reducing mail crimes with enhanced security for its collection boxes and postal locks.

“We have been unrelenting in our pursuit of criminals who target postal employees and the U.S. Mail,” said DeJoy in a March 2024 press release[40]. “We will continue to make major investments to secure the postal network while directing the full weight of our law enforcement resources to protecting our employees and the mail.”

Postmaster General Louis DeJoy meets with then-Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) on December 20, 2022, in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

Postmaster General Louis DeJoy meets with then-Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) on December 20, 2022, in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

The program includes the replacement of 49,000 antiquated arrow keys, according to a May 2023 press release[41].

However that’s just 0.5 percent of 9 million arrow keys overall — in other words, only one out of every 200 arrow keys will be replaced.

A full mailbox locking modernization program would cost more than $2.6 billion in hardware alone, according to an estimate contained in the Office of the Inspector General’s report.

The program also includes the installation of 12,000 high-security blue collection boxes through fiscal year 2024 in “high security risk areas,” the 2023 release said.

To date, more than 15,000 new high-security blue collection boxes have been replaced, along modernizing with 28,000 antiquated arrow locks" using electronic mechanisms, "with more to come," Walton said.

“As we devalue those postal keys and other postal property, we would think that criminals would move on to some other avenue away from the Postal Service,” Block said.

Letter carriers say the modernization is long overdue as the arrow key technology dates back to the 1950s, Julion said, calling the keys “antiquated at best.” Adapting fob technology similar to what’s used in hotels would be ideal, he said.

As for criminal investigations, in fiscal year 2022[42], the Postal Inspection Service handled 5,499 cases, which led to 4,291 arrests and 3,947 convictions, according to its annual report.

That’s less than a third of the arrests the Postal Inspection Service made at its peak in 1992, with 14,578 that year, according to research published by the State University of New York at Albany[43]. In 1992, the population of the United States stood at 255.4 million[44] — about 80 million people less than the nation’s current population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Postal Inspection Service arrests were greater than 10,000 each year between 1988 and 2005.

The Postal Inspection Service reported more than 1,200 arrests for letter carrier robberies and mail theft since May 2023. In the past five months, letter carrier robberies decreased by 19 percent, and mail theft complaints fell by 34 percent, the March 2024 release said[45].

The Postal Service also reported making 73 percent more arrests for letter carrier robberies than it did in the same time period last year, according to the March 2024 press release[46].

Still, the Postal Inspection Service must constantly “adapt as criminals adapt” and accept the limitations that it can’t stop every criminal, Block said.

“We're not able to be everywhere at once and also conduct criminal investigations,” Block said. “We're not a protective force. We're here as an investigative body.”

“There aren't enough postal inspectors to provide every letter carrier with around the clock protection, just as there aren't enough police officers in any city across the country to provide around the clock protection to citizens,” Block continued.

Block said lots is happening behind the scenes to keep employees safe as well.

That includes “stand-up” or “service” talks with letter carriers from postal inspectors like Block about what to do to stay safe when out on their routes. Advice often includes warning letter carriers to be aware of their surroundings, to note anything unusual on their routes and to be vigilant, he said.

“Robberies or attacking letter carriers, that's an unfortunate thing that has increased over the last few years,” Block said.

The Postal Inspection Service increased its staffing to address the increased attacks and is providing more education in case a letter carrier experiences a crime while delivering, Block said. The agency has also done a “really good job at making ourselves known to postal employees and how they can get in contact with us,” Block said, noting that there’s a 24/7 hotline both postal employees and customers can call if there’s danger (877-876-2455).

“If you do, unfortunately, end up in a situation where you become a robbery victim or a victim of some other crime while conducting your responsibilities, then the most important thing aside from trying to guarantee your safety is to be a good witness, to remember the things that could serve us well in an investigation to try and find these people and bring them to justice,” Block said.

With legislation, is it likely ‘common sense will prevail’?

Mail theft and crimes against letter carriers has grabbed the attention of lawmakers and government agencies.

Chuck Young, a spokesperson for the U.S. Government Accountability Office[47], said his agency expects to release a report about the Postal Inspection Service’s postal inspectors and postal police officers in June.

The report will examine “the extent and nature of crimes against postal employees and property” and the responsibilities of postal inspectors and postal police “in addressing serious crimes against postal employees and property” — along with the adequacy of the Postal Inspection Service’s processes, Young told Raw Story via email.

Albergo said he hopes “common sense will prevail,” and the report will spur Congress to act.

There are currently three bills in Congress that are pushing to restore postal police officers’ off-property duties, two called the Postal Police Reform Act. The latest, the Protect our Letter Carriers Act, was introduced last week.

Reps. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA) and Greg Landsman (D-OH) introduced the Protect our Letter Carriers Act, calling for more severe punishment for those who assault letter carriers and replacing outdated mailboxes and arrow keys.

“The increasing amount of robberies and assaults against letter carriers is highly concerning and ensuring their safety must be properly addressed by Congress,” Fitzpatrick told Raw Story in a statement. “We must step in to ensure that proper oversight is conducted and the resources our letter carriers need for safety are accessible.”

The House version of the Postal Police Reform Act was reintroduced in May 2023 by Rep. Andrew Garbarino (R-NY). Reps. Calvert, and Bill Pascrell (D-NJ), along with Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC), co-sponsored the bill.

Pascrell called DeJoy's tenure as postmaster general "catastrophic," and said postal employees "have been plunged into existential danger."

"Postal Police Officers are being blocked from protecting postal employees and property, leading to a spike in theft of property and frightening assaults against letter carriers. This is an absolute disgrace," Pascrell told Raw Story in a statement. "Postal employees must be shielded to go about their business. Our commonsense legislation would let brave postal police do their jobs without interference. USPS can only remain a national crown jewel when its employees’ safety and Americans’ property both are fully protected."

Sens. Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Susan Collins (R-ME) introduced the Senate bill[48] in November 2023, which has been referred to the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL) speaks at the U.S. Capitol on September 28, 2022. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL) speaks at the U.S. Capitol on September 28, 2022. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

Other co-sponsors of the bill include Sens. Jerry Moran (R-KS), Ben Cardin (D-MD), Sherrod Brown (D-OH), Ron Wyden (D-OR), John Hickenlooper (D-CO), Tammy Duckworth (D-IL), Chris Coons (D-DE), Tim Kaine (D-VA), Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) and Angus King (I-ME).

Durbin, for one, expressed frustration.

“Letter carriers perform an essential service of our government, but delivering mail has become an increasingly dangerous job. It’s shameful that Postmaster General Louis DeJoy continues to turn a blind eye to the rampant and violent crimes against his employees,” said Durbin in a statement to Raw Story. “No letter carrier should be worried about being robbed at gunpoint while on their route, which I’ve reminded Postmaster General DeJoy through numerous letters[49] on the issue.”

So, too, did Cortez Masto, who specifically blamed DeJoy, a nominee of former President Donald Trump[50], who has led a postal service cost-cutting and restructuring effort since becoming postmaster general.

“This bipartisan bill reverses Postmaster General DeJoy’s dangerous rule limiting postal police officers’ jurisdiction and will help combat an unacceptable increase in attacks on letter carriers across the country,” Cortez Masto told Raw Story in a statement. “I’ll keep working to pass this bill and make sure postal workers can continue to safely deliver the prescriptions, checks and other necessities Nevadans rely on.”

Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) speaks at t the U.S. Capitol Building on February 06, 2024. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) speaks at t the U.S. Capitol Building on February 06, 2024. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

When introducing the bill, Wyden said Congress would have to step up if DeJoy didn’t respond to the increase in crime.

“For over 200 years the United States Postal Service has been a central fixture of the American government. The recent cases of mail theft and the alarming uptick in assaults against postal workers is unacceptable,” Wyden said in a statement. “If Postmaster DeJoy refuses to act, Congress must do everything it can to improve protections for these essential workers.”

Brown told Raw Story that mail theft has affected “too many Ohioans" and "too many postal workers face threats on the job." He wrote letters to DeJoy and Inspector General Whitcomb Hull in 2022 about rising postal robberies, and after receiving no response, he wrote to the Postal Service's Board of Governors, too.

"Postal robberies and mail theft are federal crimes, and the responsibility to protect postal workers and their mail should not be pushed onto overwhelmed local law enforcement personnel across Ohio," Brown said in a statement. "Since Postmaster General Louis DeJoy has limited Postal Police Officers’ ability to do their jobs, this bill is necessary to empower the Postal Police to keep our postal workers safe and ensure Ohioans receive their mail.”

Duckworth said rising violence and crime against letter carriers in Illinois is "deeply troubling," and they should feel "safe and protected on the job without worrying their safety could be threatened at any moment," particularly when doing essential work that provides necessities to veterans, small businesses and seniors.

Duckworth said she co-sponsored the bill to "counter Postmaster General DeJoy’s reckless changes that restricted Postal Police Officers to USPS properties."

"This bill would help maximize USPS resources and help ensure these officers can better protect our letter carriers along their routes," Duckworth said. "The success of USPS depends on the ability of letter carriers to carry out their duties safely, quickly and accurately, and I will continue working with my colleagues on both sides of the aisle to pass this important legislation to support them in that mission.”

Norton, Moran and Kaine were unavailable for an interview, and all other members of Congress did not respond to Raw Story’s questions.

‘Get back to me’: Supporting letter carrier safety

Norris’ attack in January 2023 wasn’t the first time she witnessed violence in the job as a letter carrier. In 2011, she was caught in the crossfire of a drive-by shooting.

“No sooner than I started ducking, ‘pow pow pow pow,’ a barrage of bullets, gunfire,” Norris said. “It was over like 20 to 30 shots. A young man that was on the corner did die. I had to slide up under a truck for safety, and I just laid there and the gunshots stopped.”

At the time, Norris said her supervisor pushed her to finish her route that day, until her union representative stepped in. With her most recent attack, Norris said the Postal Service was more supportive, but she still feels “a bit of hurt” toward postal inspectors.

After Norris’ attack in January 2023, she didn’t return to work until the first week of May, but she was paid during that time.

“They robbed me sociably. I couldn't work. I didn’t want to be around anyone,” Norris said. “I isolated myself sociably. I didn't go to anything. No weddings, no grocery store, no parties. I became a loner. I went through a depressive stage. I stayed in the house, so they took more from me than just that key.”

Norris said she skipped her grandson’s birthday trip to Disney World last year as she was still depressed from the incident.

Workers’ compensation covered Norris’ bills for a psychiatrist, who she still continues to see today.

When Norris returned to work, her psychiatrist recommended she work inside a postal facility because of her fears of delivering mail on the streets — particularly in the winter when people are more often wearing masks.

She is fearful for her son, too, who has himself worked as a letter carrier for seven years. Norris said she calls him at least three times a day to make sure he’s safe.

“It really irks me that I can't go out there and protect them because I was once one of them,” said Barber, a postal police officer who previously worked as a letter carrier in downtown Chicago for 12 years. “At heart, I still am.”

Norris gradually worked her way up from four-hour shifts back to full-time hours, but she’s still working inside. As a self-described “people person,” Norris said she misses her customers and the peace that mail delivering used to bring her.

No arrests have been made in relation to the January 2023 attack, Block said. Lack of justice is one of the biggest concerns for Foster, the president of the Chicago branch of the National Association of Letter Carriers.

Khalalisa Norris stands on the sidewalk outside a post office in Oak Park, Ill. She has worked inside a postal facility since she was assaulted in 2023 and hopes to return to her mail route soon. (Photo by Alexandria Jacobson/Raw Story)

Khalalisa Norris stands on the sidewalk outside a post office in Oak Park, Ill. She has worked inside a postal facility since she was assaulted in 2023 and hopes to return to her mail route soon. (Photo by Alexandria Jacobson/Raw Story)

“Just want to see more prosecutions, more foot patrol out there in any kind of way they can,” Foster said. “Saturate the areas where most of the crimes are coming from to protect their letter carriers so that they can see that something is being done.”

As for Norris, she is hoping to return to her mail route in April or May — more than a year after her assault.

“I have to take my life back. I can't allow them to have me stuck here in this place,” Norris said. “It's still happening. They're still doing it, so for me it was like I need to know if this is something I can continue to do.”

References

- ^ Raw Story (www.rawstory.com)

- ^ publication (about.usps.com)

- ^ assaulted (www.kktv.com)

- ^ statute reinterpretation (www.wsj.com)

- ^ Raw Story (www.rawstory.com)

- ^ 2019 (www.uspis.gov)

- ^ 2022 (www.uspis.gov)

- ^ U.S. Postal Inspection Service’s annual reports (www.uspis.gov)

- ^ The Eagle (about.usps.com)

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (www.bls.gov)

- ^ allegedly shot and killed (www.jsonline.com)

- ^ in Milwaukee (www.jsonline.com)

- ^ WTMJ 4 (www.tmj4.com)

- ^ Inside the neo-Nazi hate network grooming children for a race war (www.rawstory.com)

- ^ in the midst (www.govexec.com)

- ^ of a (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ massive, and controversial reorganization (federalnewsnetwork.com)

- ^ ongoing financial difficulties (www.cnn.com)

- ^ nominated by the president (www.reuters.com)

- ^ The Eagle (about.usps.com)

- ^ fiscal year 2022 (www.uspis.gov)

- ^ fiscal year 2019 (www.uspis.gov)

- ^ critical report (www.uspsoig.gov)

- ^ Racism, arrests, extreme MAGA love: Meet Lauren Boebert’s primary opponents (www.rawstory.com)

- ^ alert (www.fincen.gov)

- ^ 2023 report (www.thomsonreuters.com)

- ^ check washing (www.uspis.gov)

- ^ website (www.uspis.gov)

- ^ mail theft in October (www.rawstory.com)

- ^ thief stole from the mail a $3,000 check (www.rawstory.com)

- ^ deteriorated (www.gao.gov)

- ^ decreed (www.documentcloud.org)

- ^ 2020 internal document (www.documentcloud.org)

- ^ 2020 internal document (www.documentcloud.org)

- ^ lawsuit (casetext.com)

- ^ determining (assets2.pacermonitor.com)

- ^ website (www.uspis.gov)

- ^ job description (www.documentcloud.org)

- ^ class action suit (www.classaction.org)

- ^ March 2024 press release (about.usps.com)

- ^ press release (about.usps.com)

- ^ fiscal year 2022 (www.uspis.gov)

- ^ State University of New York at Albany (wayback.archive-it.org)

- ^ 255.4 million (www2.census.gov)

- ^ the March 2024 release said (about.usps.com)

- ^ March 2024 press release (about.usps.com)

- ^ U.S. Government Accountability Office (www.gao.gov)

- ^ Senate bill (www.durbin.senate.gov)

- ^ letters (www.durbin.senate.gov)

- ^ Trump (www.rawstory.com)